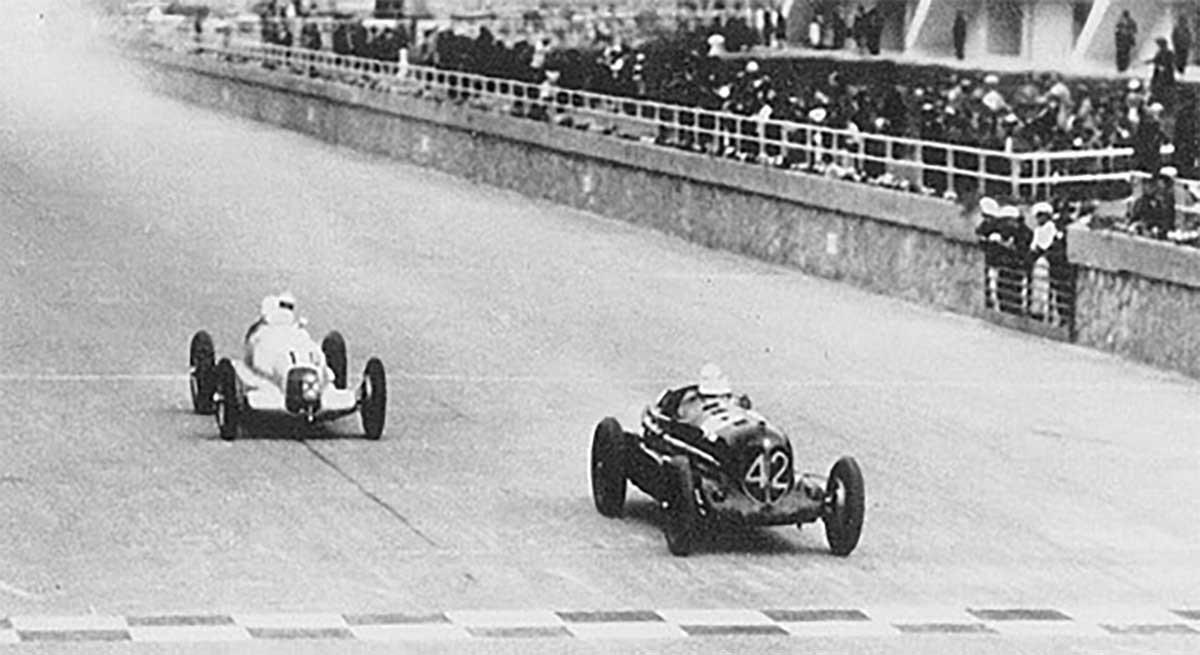

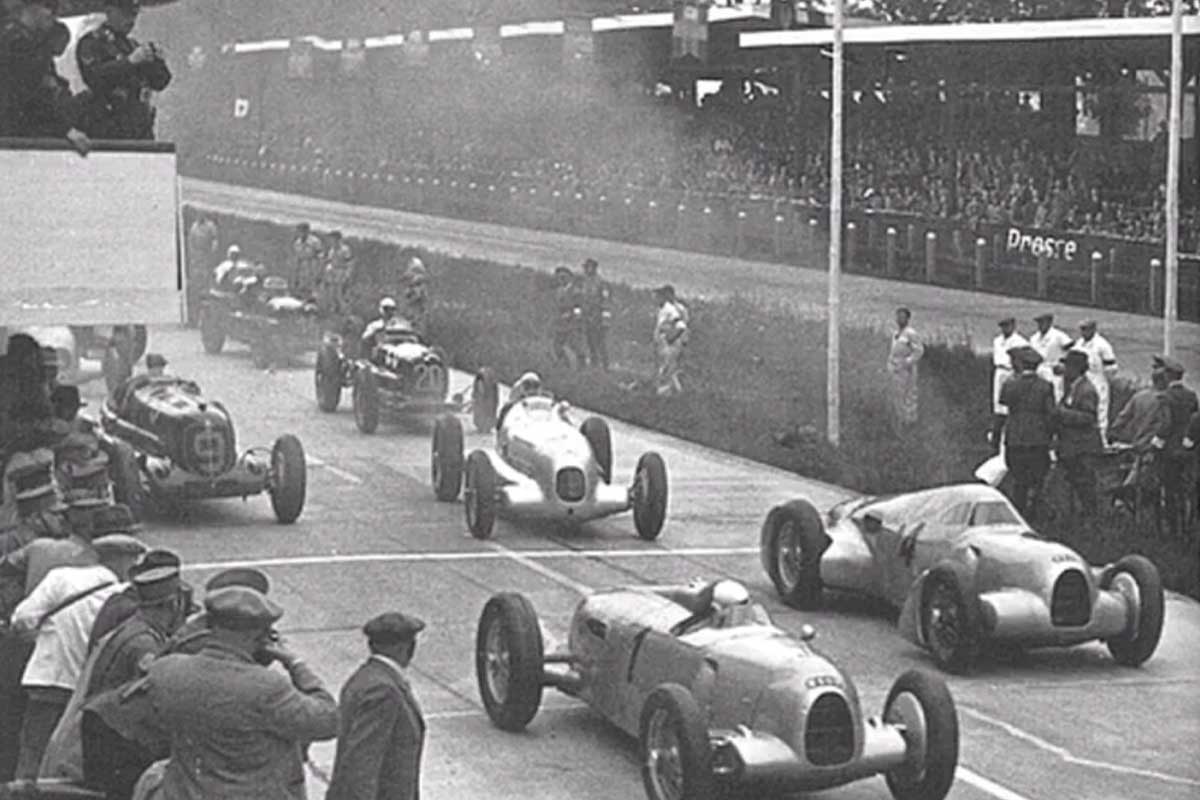

After dominating the grand prix scene in the early '30s, it was a cold shower in 1934 for Alfa Romeo. The new European championship is based on the Formula Libre system, which imposes a minimum weight of 750 kilos while allowing total freedom of choice for the engine. The Milanese marque got the season off to a flying start with victories in Monaco and the French Grand Prix, but Mercedes and Auto-Union burst onto the scene during the course of the season and reshuffled the cards.

Heavily subsidized by the Nazi regime, the two German manufacturers launched sophisticated, overpowered machines that enabled them to crush the competition. Faced with the Auto-Union Type A's 4.3-liter 16-cylinder and the Mercedes W25's 4.0-liter in-line 8-cylinder, both blithely exceeding 300 hp, Alfa Romeo found itself powerless with its valiant but aging P3, whose 8-cylinder, increased to 2.9 liters, could only contend with 255 hp.

Ferrari vs. Germany

In the mid-1930s, nationalist fervor, exacerbated by authoritarian fascist regimes, found an ideal arena for expression in motor racing. Speed, power, technology and daring were all values highlighted by motor sports, and were likely to be recuperated and instrumentalized by authoritarian regimes, eager for propaganda and patriotic exploits.

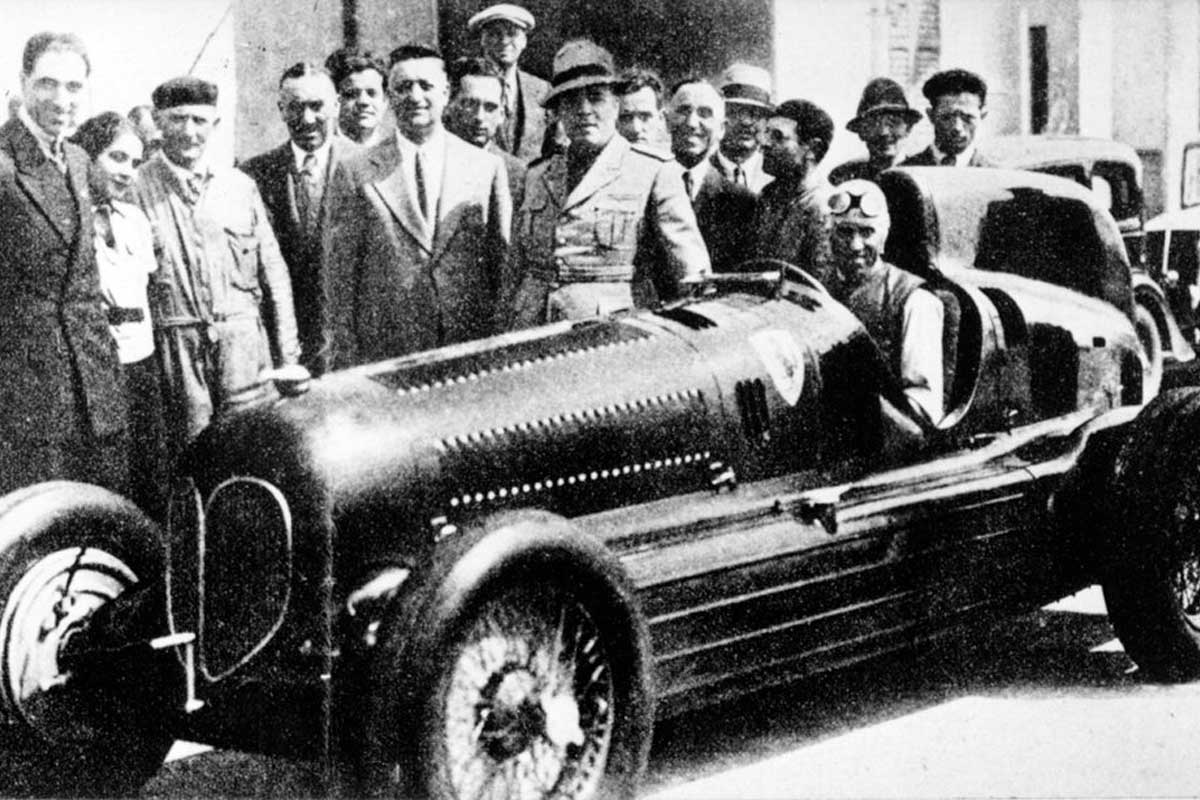

It's hard to say whether the order came directly from the highest levels of government, but Scuderia Ferrari's mission in 1935 was to strike back at Germany's insolent war machines! Since 1933, the "Commendatore"'s structure (he hated this nickname) had taken over from Alfa Corse as the manufacturer, in financial difficulties, had had to concentrate on road cars. Let's not forget that the brand was then under the control of the IRI, a state body that had been set up by the Fascist regime to save Italian banks from bankruptcy and support the national economy, at the time of the Great Depression.

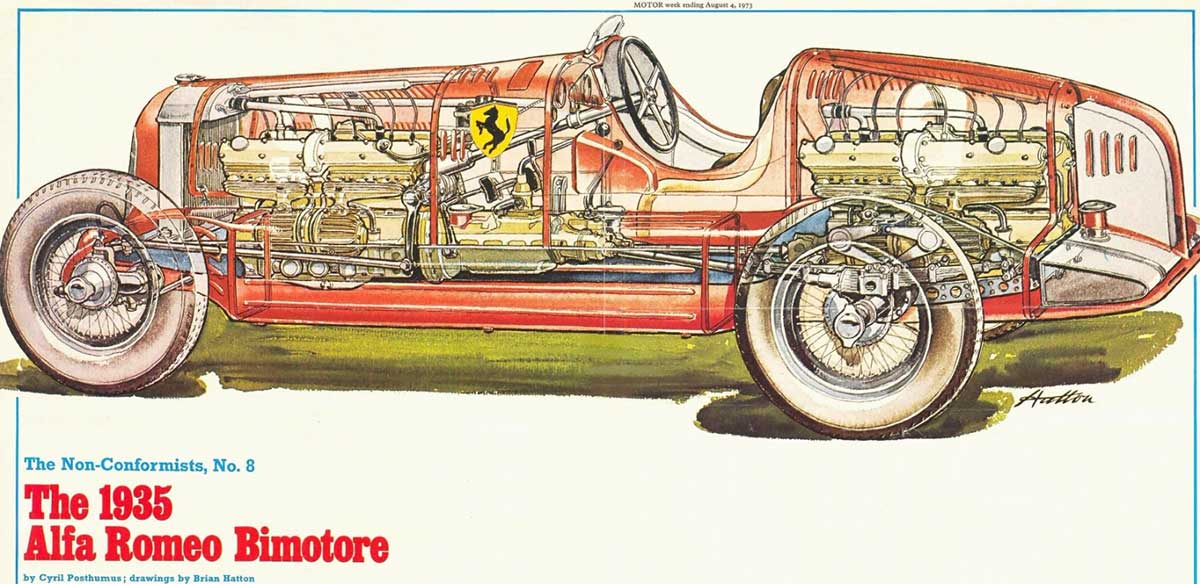

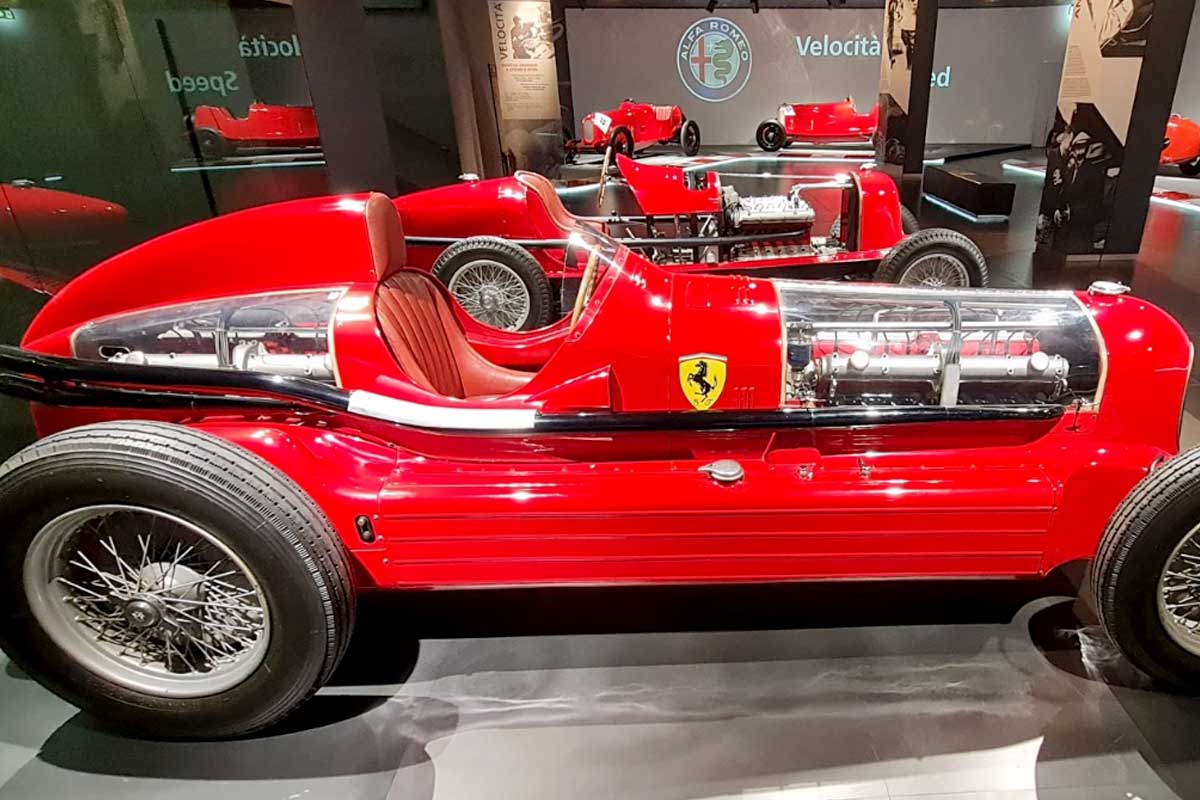

To counter Germany, Enzo Ferrari had an idea: rather than producing a new large-displacement engine, which is not really the trademark of Italian mechanical engineering, why not combine two engines? Think outside the box. After all, Alfa Romeo had already tried this in 1931 with the Tipo A, or 12C-3500, which combined two 1750cc 6-cylinders. The Bimotore concept was thus on track, but it had to move fast, as the green light was given late, in January 1935! Development had to be speeded up, in a few months at most, in order to be operational as soon as possible. Lugi Bazzi was entrusted with this delicate mission, which would be carried out in Modena, in the Scuderia workshops. The Alfa Bimotore can thus be considered the very first racing machine to be designed and produced in the Maranello workshops!

16 cylinders, but yes!

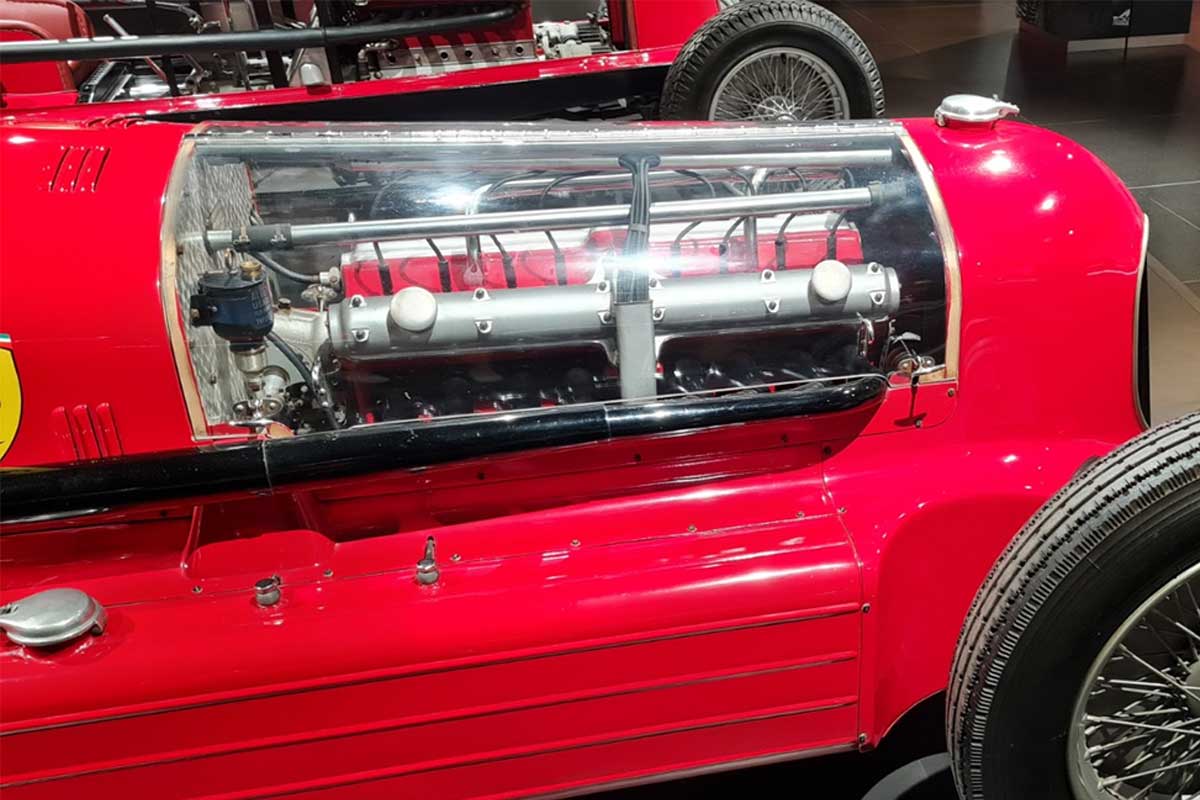

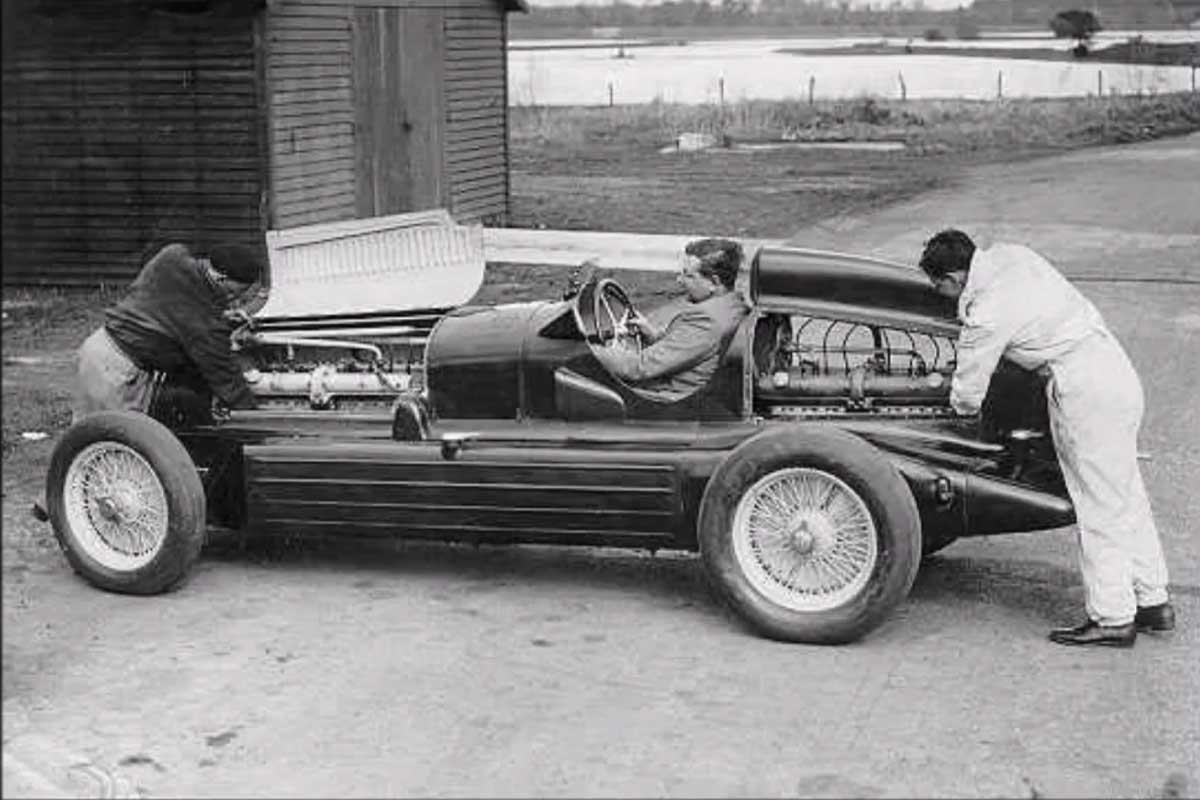

In view of the very short time available, Bazzi based the car on the chassis of the old P3 and drew inspiration from the "Aero" bodywork designed in 1934 with Breda for speed circuits. The wheelbase was lengthened by 15 centimetres to accommodate the two 8-cylinder engines. But rather than coupling them together, side by side, one is placed in front of the driver and the other, mounted upside down, behind the driver. This is a complex arrangement, as the two engines have to be linked via a long shaft, which is connected to a single gearbox and clutch. Motion is transmitted to the rear wheels via two secondary V-shafts, as on the P3.

Traction remains limited to the rear axle, which is set in motion by a differential located at the output of the three-speed gearbox. The driver's seat is relocated above the gearbox, while the fuel tanks migrate to the sides of the body, in the form of two pontoons. A mechanism under the gearshift lever enabled the driver to disconnect the engines and start them before they were synchronized, and it was also possible to drive with a single engine.

The two engines, which each develop 270 horsepower thanks to the compressors, give a displacement of 6.3 liters and a total power of 540 horsepower - 80 more than the Auto-Union! To give you an idea of these figures, we'll have to wait until the early 80s and turbocharged engines to see such power again in F1!

Bimotore bites the dust in Libya

In April, just a few months after the project was launched, the Bimotore 16C was tested on the Brescia-Bergamo freeway. While the power was there, with a top speed estimated at over 330 km/h, engineers and drivers were skeptical about the stability and agility of the monster, which, with its two engines, weighed in at just under 1,300 kilos and consumed a lot of fuel! Apart from Formula Libre, the Bimotore disqualifies itself from all other types of racing.

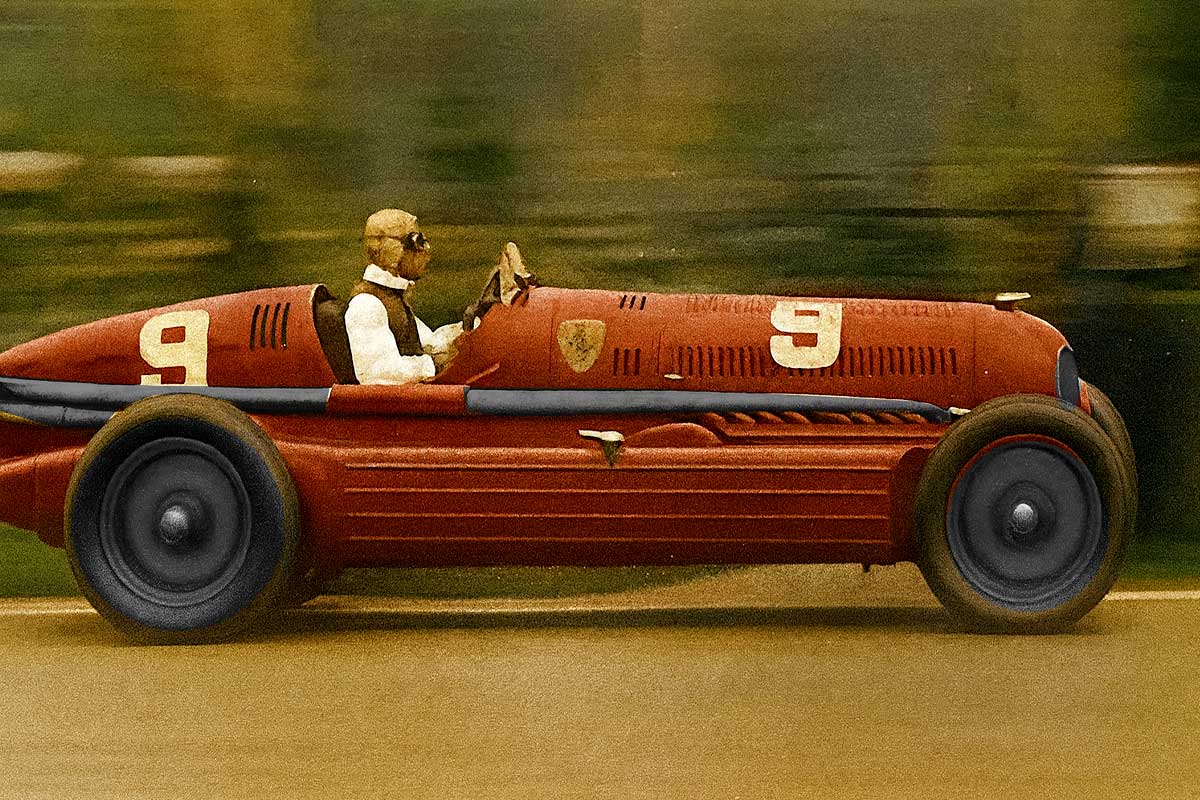

But there's no time to procrastinate. In May, the Tripoli Grand Prix takes place in the heart of the Italian colony of Libya, on the fast Mellaha circuit. The German teams will obviously be there, and Alfa Romeo has a duty to stand up to them! On "Italian" soil, the Fascist regime cannot accept a new affront. Two Bimotore were dispatched, in two variants: the 540 hp 6.3-liter was entrusted to Tazio Nuvolari, who had returned to the fold after a season with Maserati.

Legend has it that Mussolini lobbied for the intrepid driver to be rehired by Ferrari, even though the Scuderia boss and the Mantuan driver had enjoyed a tumultuous collaboration. However, the presence of Nuvolari, a driving virtuoso, is an undeniable asset. The second car is a 5.8-liter, 510hp "deflated" version for Monaco's Louis Chiron.

As soon as you try it out, you realize how difficult it is. Of course, the Bimotore is unbeatable in a straight line. But as soon as there's a bend in the road, it's not the same story! The braking system struggles to cope with the weight of the machines, forcing riders to decelerate earlier than others, even if the lighter Chiron proves more manoeuvrable. It takes all Nuvolari's skill and fearlessness to tame the 6.3-liter. The main concern is the tires!

In addition to the heat of the site, tires had to be found that could support the weight of the car at high speed and handle the enormous power, which was only delivered to the rear wheels. Dunlop tires can't handle the load. The result? A batch of Englebert tires, reputed to be stronger, was rushed by air to Libya. There was no miracle, however, as the lack of tuning was glaring. On the racing front, things quickly went from bad to worse. After a promising start, with Nuvolari overtaking Taruffi's Auto-Union to the cheers of the crowd, the Bimotore inexorably fell back! The Italian was forced to stop twice in less than 7 laps, his left rear tire bursting each time! In the end, Nuvolari stopped four times and changed 13 tires, finishing 1 lap behind the Germans. Small humiliation...

Nuvolari no longer wants it!

Alfa Romeo didn't give up, and the Bimotore was entered for the Avus Grand Prix, a very high-speed circuit with endless straights that were supposed to be better suited to the monster. But bad luck seems to be on its side. During transport of the cars and spare parts from Tripoli to Modena, a crate containing gear sets was lost. As a result, the cars had to race on the Avus with unsuitable gear ratios, unable to fully exploit the power of the engines.

The result wasn't much better. In heat 1, Nuvolari suffered an injury to his right arm caused by a loose piece of windscreen and was unable to qualify for heat 2. Louis Chiron adopted a cautious driving style and managed, without changing tires, to take 4th place, but once again a long way from the Germans. Ferrari had to face the facts, as a famous Pirelli slogan would later say: without control, power is nothing!

Nuvolari, quite annoyed with the car, put the kibosh on it: the Bimotore was too heavy, too tire-killing and too difficult to maneuver. Development was halted, and Alfa Romeo decided to return to an advanced P3, with new suspension and a 3.2-liter 8-cylinder engine. Nuvolari used it to great effect at the Nürburgring Grand Prix a few weeks later.

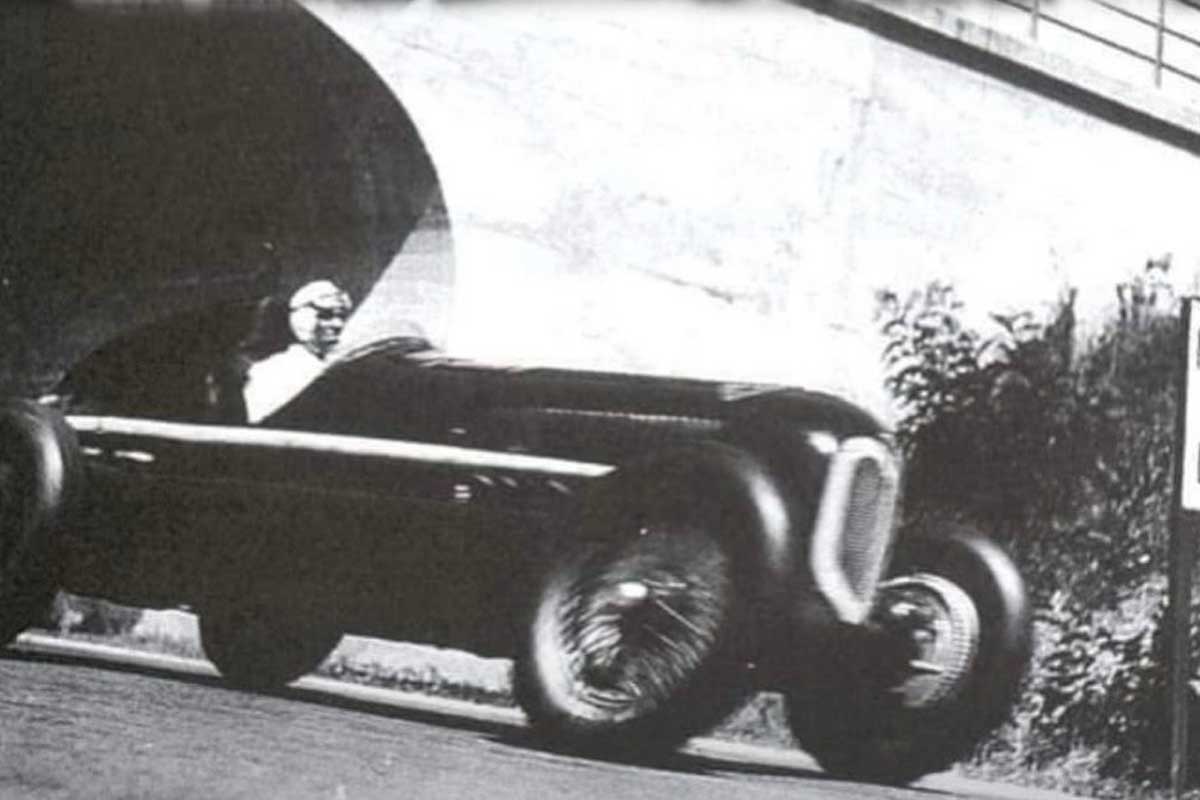

A record to leave with heads held high

However, Bimotore couldn't rest on its laurels. Nuvolari was called upon to set new records. In June, he set his sights on the speed record for the kilometer and mile thrown, on the brand-new Firenze-Mare freeway. The Flying Mantuan (perhaps the only one crazy enough to do it, of all things!) won the Class B record (between 5,000 and 8,000cc), at a speed of 321.428 km/h for the kilometer run and 323.125 km/h for the mile run, with a top speed of 364 km/h! Once this "consolation prize" had been won, the twin-engined car was definitively sent to a Scuderia Ferrari garage, before being sold to an English amateur racer, who raced it at Donington and Brooklands, albeit in a 1-motor configuration.

Man sollte diese Artikel ohne politische Wertungen veröffentlichen. Ob NS- oder Mussolini-Regime ist für den Bericht der damaligen Rennwagen völlig belanglos. Die Häufigkeit solcher Hinweise lässt den Verdacht zu, dass die Siege der Fahrzeuge relativiert werden sollen.

La storia è storia.......ed è inutile nasconderla. I riferimenti politici sono necessariamente la storia di quell' epoca è nasconderli non solo è inutile ma non dà l'idea del contesto nel quale i fatti narrati sono accaduti.

What a fascinating story!

Amazing as a concept but not practical at the time.

Rear engine was not upside down. Around the other way is what you meant